intel_fw

This is both a command-line interface (CLI) and a library for analyzing and editing firmware images for Intel platforms.

The architecture is based on knowledge from prior research.

CLI

The CLI is made with the clap command line argument parser in derive mode.

To familiarize yourself with Rust and common approaches to CLI tools, take a

look at the Rust CLI book.

For more understanding, see also any of these additional resources:

- https://rust-cli-recommendations.sunshowers.io/handling-arguments.html

- https://github.com/kyclark/command-line-rust

- https://tucson-josh.com/posts/rust-clap-cli/

- https://www.rustadventure.dev/introducing-clap/clap-v4/parsing-arguments-with-clap

Architecture and Design

The following considerations around specifics in the domain of Intel platforms and firmware are meant to offer a deeper understanding of design choices.

Goals

Separate detection from action

me_cleaner mixes both, and assessing the exact actions to happen is hard.

Via its CLI, everything a one-shot operation, and the user needs to know the

options beforehand. Note that it is very Unixesque to wrap CLIs in shell scripts

as if they were intended as APIs. That is not meant here.

For programmatic and interactive use, provide an analysis result and let the programmer/user then choose what they want to do. The programmer has to deal with all possibilities and may choose strategies around them, whereas the user can benefit from seeing the options fitting their actual case.

E.g., in a GUI app such as Fiedka or a TUI that could be created with ratatui, setting a HAP bit vs legacy (Alt)MeDisable bit(s) can be elaborated on in a help message or tooltip. Removable partitions and files can be listed rather than expected to be provided by the user who, before the analysis, doesn’t know what their firmware contains.

Comprehensible and useful API

Provide an API that requires little knowledge of internal details. The job of an API is to simplify, after all. Otherwise, both caller and callee would duplicate efforts.

Encapsulate rather than exposing many raw structs directly. Make relationships and containment clear.

E.g., wrap partition entry structs in another struct that carries supporting metadata with it, such as offset and size, parsing result of what the partition entry points to, etc..

Follow the guidelines for extending intel_fw.

Approaches

Replies to a StackOverflow question on separating preparation from execution reference the Composite pattern and the Command pattern.

The Composite pattern helps in that there is a hierarchical structure, i.e., IFD, FIT and ME firmware on a high level, and then IFD has its underlying data, the ME firmware has its FPT and partitions therein, and the FIT points to many things. Underlying details are very different though, so there are no meaningful abstractions for common interfaces.

The Command pattern may make sense on a higher level, for example, to collect the actions resulting from command line switches or API options. At the same time, it creates more boilerplate code, which may be hard to follow.

Note that we need to check the applicability of operations on two levels: Some operations exclude others, and some only apply if their assumptions fit with findings from analyzing the given firmware image.

Fiano/utk implements the visitor pattern, which is meant for objects that are quite similar in some regard.

One issue with firmware images is that while many things are related to each other, they also have their very specific purposes and semantics, and there is a rather fixed structure. It would thus be simpler to deal with specific operations on a higher level that understands the domain and carries clear semantics with it rather than having a visitor/executor encoding each possible operation for each bit and requiring more understanding from the user and programmer. I.e., just have each entity offer its own unique set of clearly understandable helpers and assisting parameters, possibly following a loose pattern when multiple entities are similar.

For example, some partitions contain directories in the case of generation 2 and

generation 3 ME:

For both generations, certain directories can be partially cleared (whole ranges

of data set to 0xff), and both can take a list of things to retain.

That requires helpers which may implement a common trait (interface).

Similarly, other partitions can be cleared, but entirely, so they do not need

extra functionality themselves. Trying to force the same interface on them only

results in unnecessary extra code.

On the other hand, the FPT itself is a small memory slice (found to be <2K), so it can take care of itself. It has a checksum in its header. Offer helpers for editing and returning a new slice to replace the original one. The IFD is similar in that it is also small, but has its own unique features. And the FIT is yet again very different.

See also the strategy pattern.

Extend with new variants and features

These guiding principles are meant to help extending intel_fw over time.

As a library, it should adhere to those as requirements in order to provide

guarantees to applications working with it. Generally, it should follow the

Rust API guidelines.

Do not panic!

Parsing firmware means looking for and acting on offsets and sizes frequently,

and they always need to be checked to stay within the bounds of the given data.

Never .unwrap() or .expect(), which mean an intentional panic, in case

something cannot be found, read, or recognized. Instead, return instances of

Self for structs, wrapped in a Result<Self, CustomError> or possibly

Option<Self>. Do not assert!() or explicitly panic!() either.

Option or Result

In general, use Option<Self> for things that might not be found. For example,

a full image from a production system would have an IFD at the beginning,

whereas an ME-only image would not. On the other hand, either image is expected

to contain an FPT, so in this case, provide a Result<Self, CustomError>,

because not finding an FPT means that something is clearly wrong with the image.

Continuous parsing

There are circumstances under which a parser encounters an issue. It can be that offsets do not make sense, magic bytes (struct markers) are not as they were expected, or new variants are found with samples not encountered before. In those situations, it is desirable to follow a best-effort strategy. I.e., when there is still remaining data that could be parsed, keep going.

Let apps provide feedback

Finally, let the consuming application take care of taking the result apart.

Nested structures can be thought of as trees, similar to ASTs in programming

languages. Whenever a node in the tree that is a parsing result turns into an

Error or None, other nodes beside it may still provide useful information.

That information helps the user of an app to understand the context and possibly

report what they are facing or look into the issue themselves.

Errors and context

In order to make sense of an error, context is important. During development, it

can be helpful to print out information right within a specific parser. However,

a final app is typically not run in development mode, but as a release. In that

moment, semantic errors will help to identify possible problems. Include offsets

and sizes (or Ranges) for the application to tell exactly where the problem

is, and it can choose to e.g. dump a contextual hex view on the data.

Additional information

To provide additional information, instead of returning an Err(String), wrap

it in an enum CustomError, i.e., for example,

enum CustomError {

TooSmall(String),

}

so you would return Err(CustomError:TooSmall(format!("{n{ bytes needed"))).

Analysis process

Analyzing (unknown) firmware means that we need to find or build tools to help

us look at the given binary. Common utilities are hex viewers and editors, such

xxd, hexdump and hexedit, or the ImHex app.

In addition, to help with unpacking, dd, unxz, unlzma and

similar utilities to cut out and decompress data are very handy.

Recognizing data

The following example shall help understanding the thought process when trying to get behind the meaning of unknown data. Mind that this takes a lot of time. It often starts with the simple question: What is this?

A first helpful step is to try to identify headers and formats. Binary data

structures often start with markers called signatures, magic bytes or numbers,

commonly four ASCII characters or significant numbers that suggest a meaning.

There are tools such as file to recognize them, as well as lists of common

file signatures and

magic bytes. Search engines and communities

are quick to assist with a first effort.

Often enough, other researchers have already performed initial work to build on top of. In the case of Intel ME generation 3 hardware, there are manifests with lots of metadata, described through what are called extensions by Positive Technologies. They have created the following utilities:

- https://github.com/ptresearch/unME11

- https://github.com/ptresearch/unME12

New extension in CPD manifest: 0x30

With ME version 15 firmware, there are new manifest extensions. The following is

a hex dump of the data described by extension 0x30, as printed by xxd.

Additional spaces and markers are there to assist the elaboration:

00196500: [fd01 0000]>[3082]01f9 a003 0201 ........0.......

00196510: 0202 0101 300a 0608 2a86 48ce 3d04 0303 ....0...*.H.=...

00196520: 301a 3118 3016 0603 5504 030c 0f43 534d 0.1.0...U....CSM

00196530: 4520 4d43 4320 524f 4d20 4341 301e 170d E MCC ROM CA0...

00196540: 3230 3131 3235 3030 3030 3030 5a17 0d34 201125000000Z..4

00196550: 3931 3233 3132 3335 3935 395a 3023 3121 91231235959Z0#1!

00196560: 301f 0603 5504 030c 1843 534d 4520 4d43 0...U....CSME MC

00196570: 4320 5356 4e30 3120 4b65 726e 656c 2043 C SVN01 Kernel C

00196580: 4130 7630 1006 072a 8648 ce3d 0201 0605 A0v0...*.H.=....

00196590: 2b81 0400 2203 6200 04aa aaaa aaaa aaaa +...".b.........

001965a0: aaaa aaaa aaaa aaaa aaaa aaaa aaaa aaaa ................

001965b0: aaaa aaaa aaaa aaaa aaaa aaaa aaaa aaaa ................

001965c0: aaaa aaaa aaaa aaaa aabb bbbb bbbb bbbb ................

001965d0: bbbb bbbb bbbb bbbb bbbb bbbb bbbb bbbb ................

001965e0: bbbb bbbb bbbb bbbb bbbb bbbb bbbb bbbb ................

001965f0: bbbb bbbb bbbb bbbb bba3 8201 0830 8201 .............0..

00196600: 0430 1f06 0355 1d23 0418 3016 8014 dddd .0...U.#..0.....

00196610: dddd dddd dddd dddd dddd dddd dddd dddd ................

00196620: dddd 301d 0603 551d 0e04 1604 14cc cccc ..0...U.........

00196630: cccc cccc cccc cccc cccc cccc cccc cccc ................

00196640: cc30 0f06 0355 1d13 0101 ff04 0530 0301 .0...U.......0..

00196650: 01ff 300e 0603 551d 0f01 01ff 0404 0302 ..0...U.........

00196660: 02ac 3081 a006 0355 1d1f 0481 9830 8195 ..0....U.....0..

00196670: 3081 92a0 4aa0 4886 4668 7474 7073 3a2f 0...J.H.Fhttps:/

00196680: 2f74 7363 692e 696e 7465 6c2e 636f 6d2f /tsci.intel.com/

00196690: 636f 6e74 656e 742f 4f6e 4469 6543 412f content/OnDieCA/

001966a0: 6372 6c73 2f4f 6e44 6965 5f43 415f 4353 crls/OnDie_CA_CS

001966b0: 4d45 5f49 6e64 6972 6563 742e 6372 6ca2 ME_Indirect.crl.

001966c0: 44a4 4230 4031 2630 2406 0355 040b 0c1d D.B0@1&0$..U....

001966d0: 4f6e 4469 6520 4341 2043 534d 4520 496e OnDie CA CSME In

001966e0: 7465 726d 6564 6961 7465 2043 4131 1630 termediate CA1.0

001966f0: 1406 0355 0403 0c0d 7777 772e 696e 7465 ...U....www.inte

00196700: 6c2e 636f 6dff ffff 0a00 0000 4800 0000 l.com.......H...

^

The first 4 bytes look like the data size (in little endian). We can quickly

see that the actual data is a bit more than 0x200 bytes, so 0x01fd is just

below that. A few bytes remain. But what comes next? The ASCII strings suggest

that it is something about certificates, often using encodings like ASN.1.

The encoding is specified in RFC5280.

For example, here we have:

30: sequence82: length in octets

Let us skip the first 4 bytes, and try to have openssl parse it, assuming DER:

dd if=unk30.bin bs=1 skip=4 | openssl asn1parse -inform der

Which yields:

0:d=0 hl=4 l= 505 cons: SEQUENCE

4:d=1 hl=2 l= 3 cons: cont [ 0 ]

6:d=2 hl=2 l= 1 prim: INTEGER :02

9:d=1 hl=2 l= 1 prim: INTEGER :01

12:d=1 hl=2 l= 10 cons: SEQUENCE

14:d=2 hl=2 l= 8 prim: OBJECT :ecdsa-with-SHA384

24:d=1 hl=2 l= 26 cons: SEQUENCE

26:d=2 hl=2 l= 24 cons: SET

28:d=3 hl=2 l= 22 cons: SEQUENCE

30:d=4 hl=2 l= 3 prim: OBJECT :commonName

35:d=4 hl=2 l= 15 prim: UTF8STRING :CSME MCC ROM CA

52:d=1 hl=2 l= 30 cons: SEQUENCE

54:d=2 hl=2 l= 13 prim: UTCTIME :201125000000Z

69:d=2 hl=2 l= 13 prim: UTCTIME :491231235959Z

84:d=1 hl=2 l= 35 cons: SEQUENCE

86:d=2 hl=2 l= 33 cons: SET

88:d=3 hl=2 l= 31 cons: SEQUENCE

90:d=4 hl=2 l= 3 prim: OBJECT :commonName

95:d=4 hl=2 l= 24 prim: UTF8STRING :CSME MCC SVN01 Kernel CA

121:d=1 hl=2 l= 118 cons: SEQUENCE

123:d=2 hl=2 l= 16 cons: SEQUENCE

125:d=3 hl=2 l= 7 prim: OBJECT :id-ecPublicKey

134:d=3 hl=2 l= 5 prim: OBJECT :secp384r1

141:d=2 hl=2 l= 98 prim: BIT STRING

241:d=1 hl=4 l= 264 cons: cont [ 3 ]

245:d=2 hl=4 l= 260 cons: SEQUENCE

249:d=3 hl=2 l= 31 cons: SEQUENCE

251:d=4 hl=2 l= 3 prim: OBJECT :X509v3 Authority Key Identifier

256:d=4 hl=2 l= 24 prim: OCTET STRING [HEX DUMP]:30168014DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD

282:d=3 hl=2 l= 29 cons: SEQUENCE

284:d=4 hl=2 l= 3 prim: OBJECT :X509v3 Subject Key Identifier

289:d=4 hl=2 l= 22 prim: OCTET STRING [HEX DUMP]:0414CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCC

313:d=3 hl=2 l= 15 cons: SEQUENCE

315:d=4 hl=2 l= 3 prim: OBJECT :X509v3 Basic Constraints

320:d=4 hl=2 l= 1 prim: BOOLEAN :255

323:d=4 hl=2 l= 5 prim: OCTET STRING [HEX DUMP]:30030101FF

330:d=3 hl=2 l= 14 cons: SEQUENCE

332:d=4 hl=2 l= 3 prim: OBJECT :X509v3 Key Usage

337:d=4 hl=2 l= 1 prim: BOOLEAN :255

340:d=4 hl=2 l= 4 prim: OCTET STRING [HEX DUMP]:030202AC

346:d=3 hl=3 l= 160 cons: SEQUENCE

349:d=4 hl=2 l= 3 prim: OBJECT :X509v3 CRL Distribution Points

354:d=4 hl=3 l= 152 prim: OCTET STRING [HEX DUMP]:308195308192A04AA048864668747470733A2F2F747363692E696E74656C2E636F6D2F636F6E74656E742F4F6E44696543412F63726C732F4F6E4469655F43415F43534D455F496E6469726563742E63726CA244A442304031263024060355040B0C1D4F6E4469652043412043534D4520496E7465726D6564696174652043413116301406035504030C0D7777772E696E74656C2E636F6D

509:d=0 hl=5 l= 0 cons: priv [ 2097034 ]

514:d=0 hl=2 l= 0 prim: EOC

Success! Next up, we need to find a suitable library to parse this data. Further development is omitted here.

Intel platforms

Over the years and decades, Intel has developed many hardware platforms1.

Since the 4-bit 4004 in 1971, they have progressed over 8-bit up to 64-bit systems, retaining a lot of backwards compatibility. Starting with the ICH7 based platforms, Intel introduced their AMT (Active Management Technology)2, an out-of-band management solution3 for remote provisioning and support.

AMT evolved with more features over time, carrying the vPro label for machines targeting the business market4 and finally converging with more security features such as Boot Guard5, Intel’s secure boot implementation, digital content protection (DRM), and more6.

Now running on a coprocessor called the (Converged Security and) Manageability Engine7, or (CS)ME for short, henceforth abbreviated as ME, a full second operating system of its own is backing the platform.

Boot flow

The ME has its own firmware and bootstraps an Intel platform8. The main x86 cores are held in reset until the ME releases them to boot with their own firmware.

Both the ME firmware and the main x86 firmware are stored in the same flash part on a mainboard, partitioned via the Intel Flash Descriptior (IFD).

The following diagram is based on knowledge from various sources, including the coreboot documentation on Intel.

The boot flow for trusted boot is documented publicly9 by Intel.

ME classification and security

Security researchers have analyzed the ME10 and divided hardware variants into 3 generations11 thus far, each with their own multiple firmware versions, including security patch releases12 13. One core aspect in security research has been Boot Guard14 15, which had been introduced with Haswell, Intel’s 4th generation Core series platforms16, and discussed in the coreboot community17.

Note that the ME generations roughly correspond with the overall platform, in that ranges of Intel platforms are expected to carry a certain ME hardware generation and specific platforms a certain firmware version range. For example, Lenovo ThinkPad X270 laptops came with 6th/7th gen Intel Core processors, which means 3rd generation ME hardware and version 11.x.x.x ME firmware.

Processor names

Intel publicly documents how to interpret procesor names18 and what their suffixes mean19.

Abbreviations

| abbr. | expansion |

|---|---|

| ACM | Authenticated Code Module |

| AMT | Active Management Technology |

| CSME | Converged Security and Manageability Engine |

| DAL | Dynamic Application Loader |

| FIT | Firmware Interface Table |

| FPT | Firmware Partition Table |

| HAP | High-Assurance Platform |

| {I,M,P}CH | {I/O,Memory,Platform} Controller Hub20 |

| IFD | Intel Flash Descriptor |

| PTT | Platform Trust Technology |

| RBE | ROM Boot Extensions (part of ME firmware) |

| SPS | Server Platform Services |

| TXE | Trusted Execution Engine |

| TXT | Trusted Execution Technology |

Ambiguities

There are colliding acronyms, even within this domain. The following abbreviations have a second meaning:

- FIT: Flash Image Tool (sometimes also called FITC)

- FPT: Flash Programming Tool

-

https://www.amplicon-usa.com/actions/viewDoc.cfm?doc=iAMT-white-paper.pdf ↩

-

https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/architecture-and-technology/vpro/overview.html ↩

-

https://edc.intel.com/content/www/us/en/design/ipla/software-development-platforms/client/platforms/alder-lake-desktop/12th-generation-intel-core-processors-datasheet-volume-1-of-2/010/boot-guard-technology/ ↩

-

https://www.intel.com/content/dam/support/us/en/documents/technologies/intel_amt_linux_enablement_guide_revision_1_1.pdf ↩

-

https://i.blackhat.com/USA-19/Wednesday/us-19-Hasarfaty-Behind-The-Scenes-Of-Intel-Security-And-Manageability-Engine.pdf ↩

-

https://www.intel.com/content/dam/www/public/us/en/security-advisory/documents/intel-csme-security-white-paper.pdf ↩

-

https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/developer/articles/technical/software-security-guidance/resources/key-usage-in-integrated-firmware-images.html ↩

-

https://bitkeks.eu/blog/2017/12/the-intel-management-engine.html ↩

-

https://papers.put.as/papers/firmware/2014/2014-10_Breakpoint_Intel_ME_-_Two_Years_Later.pdf ↩

-

https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/support/articles/000029389/software/chipset-software.html?wapkw=csme ↩

-

https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/support/articles/000055675/technologies.html?wapkw=csme ↩

-

https://prohoster.info/en/blog/administrirovanie/doverennaya-zagruzka-shryodingera-intel-boot-guard ↩

-

https://web.archive.org/web/20201129154607/https://www.intel.com/content/dam/www/public/us/en/documents/product-briefs/4th-gen-core-family-mobile-brief.pdf ↩

-

https://web.archive.org/web/20230322090345/https://patrick.georgi.family/2015/02/17/intel-boot-guard/ ↩

-

https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/processors/processor-numbers.html ↩

-

https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/support/articles/000058567/processors/intel-core-processors.html ↩

Knowledge on Firmware Images for Intel Platforms

The knowledge here focuses on firmware images, their partitioning and data structures.

Official resources

Intel publishes general information on firmware in their developer portal: https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/developer/topic-technology/firmware/overview.html Note that the public information mainly focuses on host processor firmware.

Other projects

me_cleanerwiki- ME Analyzer

- coreboot

- UEFITool

- Positive Technologies research

Research

Many researchers have looked into the Intel Management Engine over the years and presented on their findings:

- https://media.ccc.de/v/34c3-8762-inside_intel_management_engine

- https://media.ccc.de/v/36c3-10694-intel_management_engine_deep_dive

Forums

People keep asking in Intel’s community forum for tools and information around Intel platform firmware, resorting to third-party forums because Intel does not publish what they need or limits access to necessary resources to certain customers only, notably not end users. Here is a short list of places to find useful information and tools.

- Win-Raid (Level1Techs) Forum

- Badcaps Forum

- Indiafix Forum

- Vinafix Forum

- AliSaler

- mostav02’s notes on FPT and removals

Extraction

For older FIT tools, use binwalk to extract resources and then grep for

LayoutEntry to find descriptions of straps, which include the HAP bit, e.g.:

<LayoutEntry name="PCH_Strap_CSME_CSE_HAP_Mode" type="bitfield32"

value="0x0" offset="0x68" bitfield_high="16" bitfield_low="16" />

Note that later generation XML files just call the HAP bit “reserved”. Educated guessing by looking at neighboring bits will help you to locate it.

Newer FIT tools (e.g., v18) contain Python code that can be extracted with

pyinstxtractor. Relevant

code is in the plugins/ directory:

pyinstxtractor.py ../mfit_18.exe

ls -l tools.exe_extracted/plugins/

Firmware images

There are multiple ways of obtaining firmware images:

- read out from one’s own mainboard, e.g. using

flashprog - download from a vendor; however, those are mostly upgrade images, not the same as what would be found on real hardware, usually in a proprietary format

- download from an archive, obtain a full backup image, or similar

Full images

ChromeOS

The coreboot project offers a utility to download full

recovery images for ChromeOS (Chromebooks) including a base system and firmware,

and extract the firmware image:

util/chromeos/crosfirmware.sh

To download all the images and extract the firmware, run:

./crosfirmware.sh all

As of the time of writing this, that will download: https://dl.google.com/dl/edgedl/chromeos/recovery/recovery.conf

Which looks somewhat like this:

recovery_tool_version=0.9.2

recovery_tool_linux_version=0.9.2

recovery_tool_update=

name=Dell Chromebook 13 (3380)

version=15393.58.0

desc=

channel=STABLE

hwidmatch=^ASUKA .*

hwid=

md5=9e3788b775f0c55f37682a6db6add00a

sha1=b54a3762e22d08dc3b67846e3ab16bd7333e519d

zipfilesize=1275561266

file=chromeos_15393.58.0_asuka_recovery_stable-channel_mp-v2.bin

filesize=2330960384

url=https://dl.google.com/dl/edgedl/chromeos/recovery/chromeos_15393.58.0_asuka_recovery_stable-channel_mp-v2.bin.zip

and so on. Each entry is about 12 lines. How much is in there?

wc recovery.conf

9186 11369 297858 recovery.conf

More than 650 images?! … no, there are lots of duplicates. But not exactly. Some recovery images contain firmware for multiple devices!

grep url= recovery.conf | uniq | wc

76 76 9310

A good bunch of downloads would fail, though. I reduced the script to fewer entries. Note that Chromebooks may be based on any platform, not only Intel.

How many images that you downloaded are for Intel?

for f in coreboot*.bin; intel_fw me scan $f; end 2>&1 | grep 'No ME' | wc

19 133 1235

The remaining images can now be used to test intel_fw.

Win-Raid Forum

Many samples can be found via this forum post: https://winraid.level1techs.com/t/intel-cs-me-cs-txe-cs-sps-gsc-pmc-pchc-phy-orom-firmware-repositories/30869

Unpacking Firmware

Firmware images are typically packed and consist of various pieces henceforth called components. In different places, they may be called more specific terms, such as partitions, directories, modules, files, etc.

Many components are containers, which in turn are comprised of other things. As it happens over time, a firmware image for a platform of today may look very different from one meant for a platform from the past. It may be, however, that the target platform cannot be recognized right away, making analysis harder. Such is the case for Intel. We thus need an architecture that is able to distinguish at any given level and allows for extraction.

Partitions

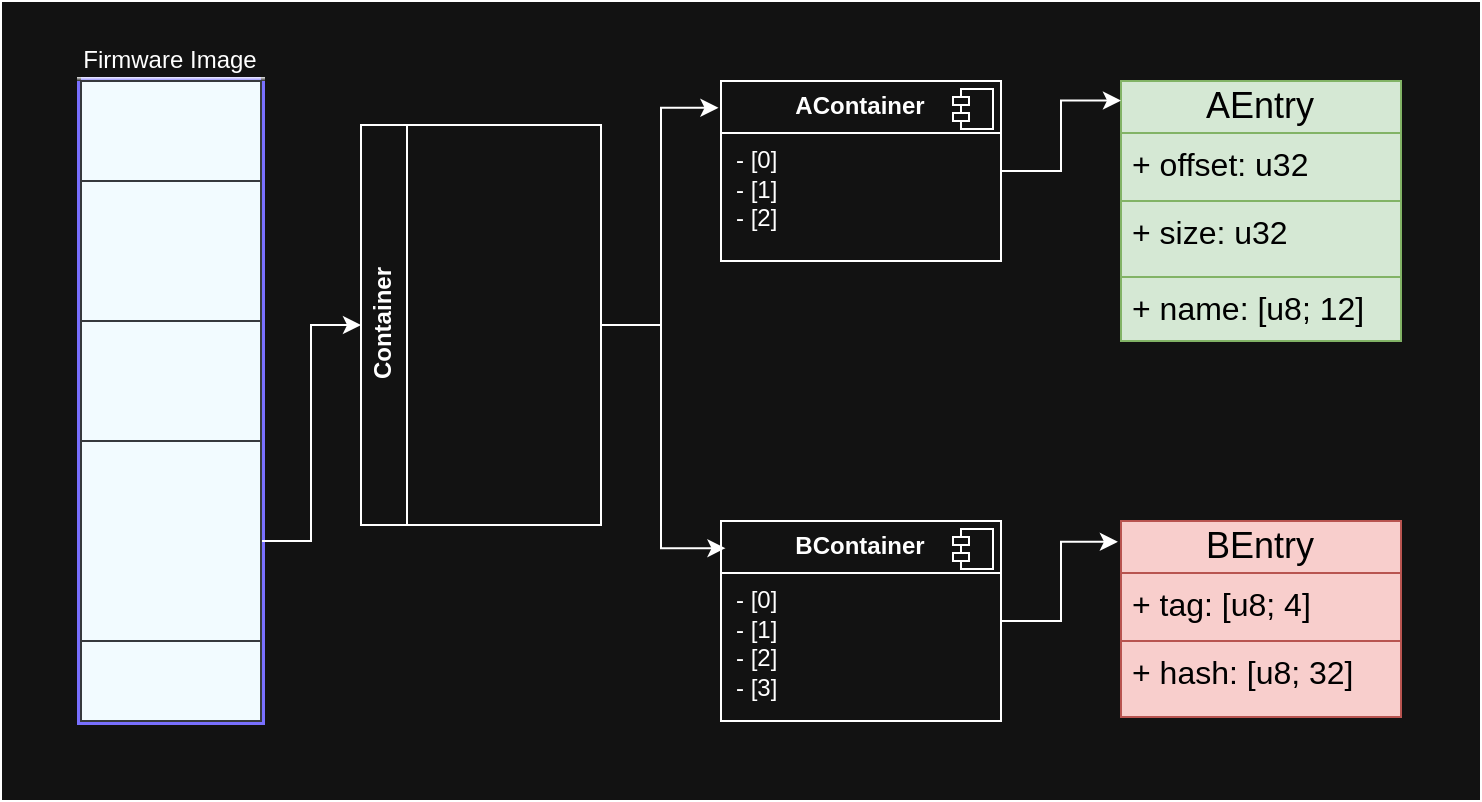

The following diagram is a generic example of a partitioned firmware image with a container that may be of either one or another kind. And in turn, it would contain one or another kind of entries.

In Rust, we can use enum

types to express this:

enum Container {

AContainer(Vec<AEntry>),

BContainer(Vec<BEntry>),

}

Intel ME Generation 2

With the second hardware generation, Intel ME based platforms have introduced

a partitioning scheme called Flash Partition Table (FPT), starting with a $FPT

magic. There are code and data partitions, and the main code partition is called

FTPR.

Code partitions start with a manifest that holds metadata over the modules contained in the partition, as a flat directory. Those modules are in part Huffman-encoded and chunked, and the Huffman tables are part of the mask ROM.

The overall manifest format is header + signature + data. The data part lists the modules with their offsets, sizes and hashes, so that the manifest covers the whole partition’s integrity.

Intel ME Generation 3

With the third hardware generation of Intel ME based platforms, a new operating system was introduced, based on MINIX 3. It needs bootstrapping first, starting with phases called RBE (ROM Boot Extensions) and bup (bringup).

There are multiple kinds of partitions, including Code Partition Directory (CPD) partitions. Those contain executables, their corresponding metadata files, and a manifest that holds a signature over the header before it and its other data. The manifest format with the header and signature is the same as for Gen 2.

The signed data in the manifest includes hashes of the metadata files and other things, so that the manifest suffices to verify the entire CPD’s integrity. Each metadata file contains the counterpart binary’s hash. The binaries themselves are mostly compressed, commonly using LZMA and a few via Huffman encoding.

Knowledge on CPDs, manifests, metadata and binaries can be found in PT Research utilities for unpacking:

Integrated Firmware Image

A variant of ME gen 3 firmware exists based on a different layout, as described in the Atom E3900 series platform enabling guide1:

The IFWI region in SPI flash physically follows the SPI Flash Descriptor Region. It contains all platform firmware components and device firmware components.

The IFWI region is divided into two Logical Boot Partitions, which are identical in size. The Logical Boot Partition layout is defined by the Boot Partition Descriptor Table (BPDT) at the head of the Logical Boot Partition.

There are multiple IFWI data structures, and some do not have a magic to detect, so parsing them is not trivial. ME Analyzer has a lot of logic2 for them. In some cases, the FPT is located right after the IFWI.

The BPDT entries mostly point to CPDs, including the FTPR. Some BPDT entries may point to the FPT.

Samples:

- BPDT v1: Google “Coral” Chromebook

- BPDT v2: System76 Lemur Pro 10 (Tigerlake), Gigabyte Z5903